Iconic 1980s Fashion Brand Benetton Exits Japanese Market

Benetton pioneered the use of multiracial models and was known for its signature bright primary colors. It undoubtedly had an outsized influence on competing brands Zara, H&M, and Uniqlo.

What’s new: Big hair, neon colors, shoulder pads, leg warmers, acid-washed jeans, MTV, synth-pop, high-top sneakers, graphic T-shirts, and the ubiquitous clothing brand Benetton were all indelible icons of the 1980s. Benetton just announced on its official Instagram account that it has exited the Japanese market as of October 23, 2024, marking the end of an era and the final chapter in a saga of corporate hubris followed by decades of missteps. The brand is no longer available on its official online store or on the online e-commerce marketplaces of Zozotown and Rakuten Fashion.

Context: United Colors of Benetton (“Benetton”) is an Italian casual fashion brand founded in 1965. Its global popularity skyrocketed in the 1980s, but Benetton continued to dominate the Japanese fashion scene until the early 1990s.

Benetton Japan, the Japanese subsidiary of Benetton, opened its global flagship store in Tokyo's high-rent Omotesando fashion district near Harajuku (think Gwen Stefani's "Harajuku Girls") in December 2000. With three floors from the basement to the second floor, the store covered over 1,000 square meters (approximately 10,750 square feet), making it the first large-scale apparel outlet in Japan and a forerunner of the large flagship stores that top Western fashion houses and clothing companies have continued to build in the Omotesando area.

According to a transcript of a lecture given in 2000 by Takashi Endo (遠藤嶂), who joined Benetton Group S.p.A. in 1986 and became president of Benetton Japan when it was established in 1987, the Italian headquarters had sales of 213 billion yen (about $1.4 billion at today's exchange rate) and a net profit of 18 billion yen ($117 million) in the fiscal year ending December 1999. The company had 7,000 stores in 120 countries worldwide, and its annual production volume was 100 million items. It had about 400 stores in Japan, and its sales in Japan accounted for about 5% of its total sales (about 10.6 billion yen, or $69 million).

The sales per store may seem low, but the company operates stores worldwide through franchising and uses distributors for sales (including wholesale sales to retailers through distributors), and the company's sales are reported at the prices at which their products are shipped from their own factories. At the time, Benetton Group S.p.A. was one of the world's leading apparel companies in terms of sales (for comparison, in 1999, the sales of Fast Retailing, Uniqlo's parent company, were only 111 billion yen, or $724 million).

By the turn of the century, fast-fashion brands like Zara and H&M, as well as the now-dominant casual-fashion competitor Uniqlo, had become popular, and Benetton's franchise system was showing signs of obsolescence. In addition, the investment in stores was left up to the individual franchisees, who were struggling to keep up with the competition. The parent company began a new strategy of purchasing real estate in major cities such as Paris and New York and developing large-scale stores, leaving management to local franchisees. The flagship store in Omotesando, Tokyo, was part of this global strategy.

The global flagship store strategy failed and eventually strangled the company.

Benetton's huge outlet in Shinsaibashi, Osaka's equivalent of Shibuya, closed in 2011. In 2014, the original flagship store in Omotesando was closed. Its other stores around the country also closed one by one.

Go deeper: Company founder Luciano Benetton was born in 1935 in Treviso, a small town in northern Italy near Venice. After the war, the textile industry flourished in northern Italy, and since his sister Giuliana worked in a knitwear factory, he began producing and selling knitwear in 1955.

In 1965 the company opened a knitwear factory, and in 1968 it opened its first store in Montebelluna, Northern Italy. The colorful knitwear, made from a blend of angora and long-pile yarn in 12 different colors, quickly became popular, and the following year the company opened its first overseas store in Paris.

In the 1980s, exports expanded greatly. The export ratio, which was 2% in 1978, grew to 60% by 1986. Benetton entered the Japanese market in 1982, signing a contract with the Seibu Department Store. Takashi Endo was the first general manager of the Milan branch of the Seibu Department Store, and he was the man who first introduced such prestigious Italian brands as Benetton, as well as Giorgio Armani, Missoni, Gianfranco Ferré, and Dolce & Gabbana to Japan.

After its establishment in Japan in 1985, the company rode the wave of the bubble economy, the import brand boom, and the F1 racing boom, for which it owned a team, and became popular among young people for its Italian-style colors and affordable price range.

By the mid-1990s, however, minimalist and street fashion had become popular, and Benetton's bright, 1980s-style creations were out of touch.

In the 2010s, the company's performance continued to decline, and in 2012, founder Luciano Benetton stepped down as representative director, and his son Alessandro Benetton was appointed as his successor. In 2014, the company welcomed Francesco Gori as its first non-family executive president, but business performance did not recover.

In 2018, founder Luciano returned to the position of representative director, and veteran Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, known as the magician of color, was appointed artistic director. But it was too little, too late.

In 2022, former Tod's designer Andrea Incontri was appointed creative director, and in 2023 he presented a show at Milan Fashion Week for the spring/summer season. It was a flop, and he resigned in August 2024.

Why it matters: While the rise and fall of Benetton makes for a good story and would certainly make for a fascinating case study at Harvard Business School, it's the brand's outsized influence on key trends in casual fashion and advertising that will be remembered.

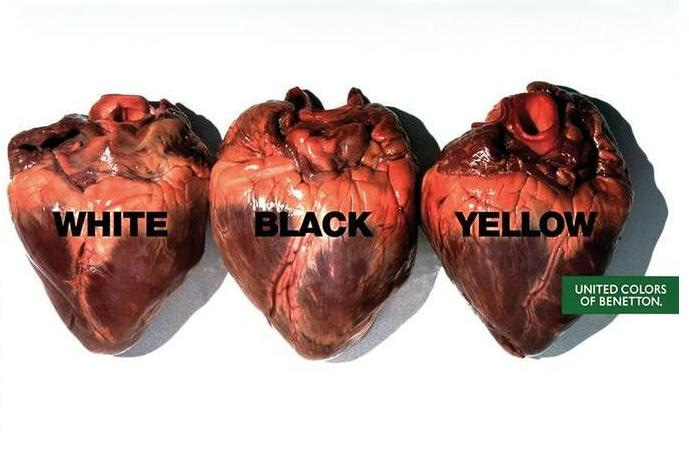

Benetton's advertising campaigns by photographer Oliviero Toscani attracted a lot of attention. This revolutionary artist was one of the first globally revered photographers to champion diversity, inclusivity, and gender equality. Toscani's campaigns often featured diverse individuals, including people of different races, ethnicities, and sexual orientations. This challenged traditional beauty standards and stereotypes prevalent in advertising. His work often focused on social and political issues such as AIDS, racism, and immigration. By featuring real people from marginalized communities, he humanized these issues and promoted empathy. Toscani's campaigns often blurred gender lines, featuring models who defied traditional gender roles. This challenged societal expectations and promoted a more fluid understanding of gender identity. His work often employed an androgynous aesthetic, where models were styled in a way that did not clearly identify their gender. This challenged the notion of binary gender and promoted a more inclusive approach to beauty.

What’s next: Benetton's future looks promising with its focus on sustainability and e-commerce. The company has committed to using 100% sustainable cotton by 2025 and has reduced its production volume to prioritize quality and sustainability.

Benetton's parent company, Edizione, is flush with cash and delivers solid financial results. Founded in 1981 as a holding company for the Benetton family, the company has interests in transportation infrastructure, digital infrastructure, financial institutions, food and beverage, travel, retail, real estate, agriculture, apparel and textiles, and a host of other businesses. It is one of the leading holding companies in Europe, with sales of 1.5622 trillion yen ($10.2 billion) in fiscal 2023 and a net asset value of 1.924 trillion yen ($12.5 billion) as of December 31, 2023.

In addition, Benetton is expanding its online presence with a new U.S. e-commerce platform. While challenges such as competition and economic uncertainty exist, Benetton's strong brand heritage, social responsibility initiatives, and strategic approach position it for long-term success.

Whether that means a return to Japan at some point is anyone's guess. There are some who argue for a revival in terms of design, product positioning - including pricing - and materials. Don't hold your breath, but it wouldn't be too surprising to see Benetton make a triumphant return to Japan at some point, although Tokyo's Harajuku girls may have to settle for online shopping.

Links to Japanese Sources: https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/836964 and https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/a2df68ef004623291101074774681a51d4e2c50a.

#Benetton #UnitedColorsofBenetton #ItalianCasualFashionBrand #ExitJapan #CasualFashion #FastCasual #BenettonJapan #Zara #Uniqlo #FlagshipStore #diversity #inclusivity #genderlessness #OlivieroToscani #AndrogynousAesthetics #Edizione #ベネトン #ユナイテッドカラーズオブベネトン #イタリアのカジュアルファションブランド #カジュアルファション #ファストカジュアル #ベネトンジャパン #ザラ #H&M #HandM #ユニクロ #旗艦店 #オリビエーロトスカーニ #インクルージョン #中性 #無性別 #中性美 #男女両性的美学 #エディツィオーネ

Oh, that's rather sad; but, looking at Uniqlo, it seems that there is no market in Japan for colorful clothing, only drab, lifeless shades of nothing. Blah!

Fascinating article, Mark. I completely missed this development.

I remember their large stores in Osaka and Tokyo well. My main office in Osaka was in Shinsaibashi in the 1980s, and I photographed street fashion on the streets of Harajuku in the first decade and a half of this century.

Their ads did indeed leave a big impact at the time and were discussed in detail by the news media, often branded “controversial.”

How times have changed, I doubt they would be considered controversial today…