Discover more from Real Gaijin

In Japan Maybe You Can “Keep ‘Em Down on the Farm”

There is mounting demographic evidence that internal migration is slowing to a snail's pace compared to the past.

What’s new: Based on recently released census data, it appears that the number of people in Japan who never migrate to another part of the country is increasing. In other words, the number of people who are born, grow up, and stay in the countryside all their lives is actually increasing. In addition, the number of young people who have moved to other prefectures1 in the past five years is declining.

Why it matters: While it is no longer necessary to leave the countryside to earn a decent income and enjoy a reasonably good lifestyle, those who move to the cities tend to be limited to those with special qualifications, financial assets, or a certain ruthless self-confidence. Just as the idealization of rural life in Japan is not a new phenomenon, as highlighted in the long-running bestselling book series Nihon-no-Shikaku「日本の死角」, which translates as "Japan's Blind Spot," there has recently been a growing belief that people who choose to remain in the countryside are expected to be more obedient than ever to local relationships and customs. As a result, hierarchical relationships that could almost be called "local castes" have become more pronounced in rural areas.

Another reason why it is worth taking a closer look at what is behind the statistics is that Japan is often used as a benchmark to measure the pace of internal migration patterns in countries that have followed in the footsteps of Japan's economic development. Think of South Korea...or, more recently, internal migration trends in India.

By the numbers: At the beginning of each calendar year, internal migration statistics are published for the previous year. These data are based on the Basic Resident Ledger maintained by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Detailed records of the number of people who moved in and out of each prefecture and municipality are meticulously collected.

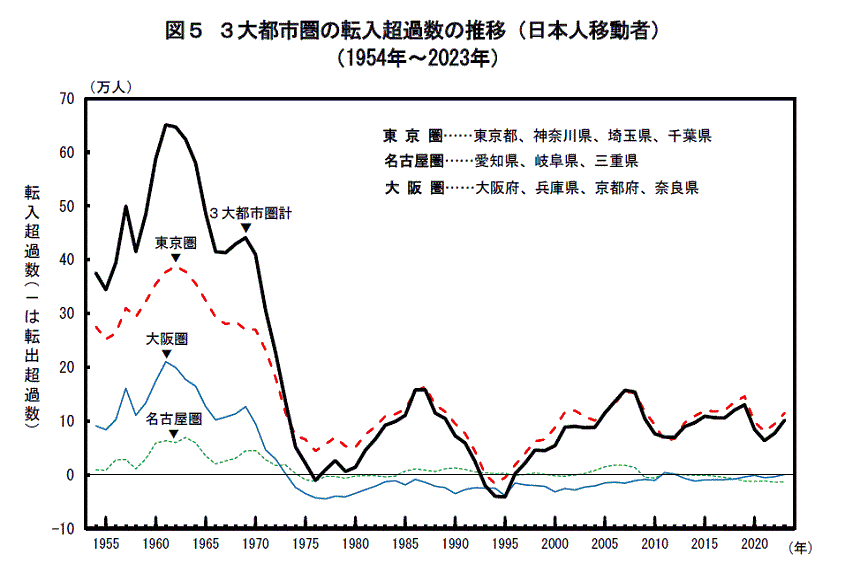

Long-term Decline since 1970: Looking at the population that has moved to the three metropolitan areas of the Tokyo metropolitan area, the Kansai region, and the Nagoya metropolitan area, as well as the migration rate divided by the total population, confirms that the number of migrants and, to a lesser extent, the migration rate have been on an almost continuous downward trend since the peak in 1970. For most Japanese, the fact that the trend has been downward since 1970 may come as a surprise.

Half the Historical Number of Migrants: The most recent figure of 680,000 in 2020 is less than half of the peak of 1.58 million, but this follows the general trend that began many years ago rather than the impact of the global pandemic.

Reason #1 – Aging Population: One reason for the decline in the number of people moving to the three major metropolitan areas is the declining birthrate and aging population. Japan has a high rate of migration among young people in their late teens and twenties. So just do the math; the denominator is smaller than it used to be. Not surprisingly, as the number of young people declines due to the declining birthrate, the number of migrants will decline accordingly.

Reason #2 - More to the Story: However, this is not the only reason for the decline in internal migration. The number of young people who have moved to other prefectures within the past five years is also on a downward trend. In particular, the decline in the migration rate of young people aged 15-19 is striking: at 0.41 times the 1970 level, it is much lower than the overall migration rate (0.51 times).

Unpacking the Chart: There is a lot going on in this graph. The x-axis shows a time line by year from 1953 to 2023. The y-axis is the number of people, but the unit is "man" (万人), which is a unit of 10,000 people, which is a common unit of measurement in East Asia. Thus, 40 on the graph means 400,000 people. Data points above zero on the y-axis indicate that more people moved in than out. Similarly, data points below zero on the y-axis indicate that more people moved out than in. The solid bold black line is the sum of all 3 of Japan's most populous metropolitan areas combined. The dashed red line is for the Tokyo metropolitan area, which includes the prefectures of Tokyo, Kanagawa, Saitama, and Chiba. The solid blue line is for the Kansai region, which includes the prefectures of Osaka, Hyogo (Kobe), Kyoto, and Nara. The dotted green line is for the Nagoya metropolitan area, which includes the prefectures of Aichi, Gifu, and Mie. It can be seen that the peak of migration occurred in the early 1960s, which would correspond to the period of the so-called "Japanese economic miracle," a time of rapid development and industrialization. Since the mid-1970s, the population of both the Kansai region and the Nagoya metropolitan area has been relatively stable, while the Tokyo metropolitan area has seen steady growth (with a few exceptions or dips along the way).

Go deeper: All of these numbers can be sliced and diced in many different ways.

Inter-City Relocation: In terms of the number of people moving between municipalities, 29.7% of the 1,719 cities, towns and villages in Japan2 had more people moving in than out. That is, 70.3% more people moved out than moved in, or a ratio of 3:7.

Geographic Growth vs. Stagnation: The 23 wards of central Tokyo had the largest number of in-migrants, followed by Osaka, Yokohama, Sapporo, Fukuoka, Saitama, Kawasaki, and Chiba, in that order. However, Chigasaki City, which ranked 26th last year, is the ninth most populous city, followed by Hiratsuka City, which ranked 25th last year. This shows that the number of people moving to the Shonan area in Kanagawa Prefecture is increasing.

Cross-Tabulation by Age: Interesting results can also be seen when the population is divided into three age groups (0-14 years: young people, 15-64 years: the “producer” group, and 65 years or older: the elderly group). Tokyo's 23 wards have by far the largest number of new residents in the 15-64 age group, 74,309, far ahead of Osaka City's 16,171 in second place. Sapporo and Fukuoka ranked first and second, respectively, in the number of migrants aged 65 and over, showing the characteristics of cities with growing populations as the main city of Hokkaido and the central city of Kyushu, respectively.

What's happening? According to some of the authors of the so-called Nihon-no-Shikaku series, there is a growing polarization between those who can move and those who cannot. Often, those who lack the resources or motivation to move tend to be people who live in rural areas. The decline in mobility deprives people of the opportunity to change their existing circumstances. The result is a society in which parental status and childhood relationships are more important than ever.

A secondary result is a polarized scene in rural communities. It is always a certain group of people who make a big show of themselves in bars and in "community development," and those who do not, who are "forced" to live quietly in their hometowns.

What's next: According to Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank's research department, recently released government data have been used to develop selected long-term population projections.

Central Tokyo: The estimated peak year for the population of Tokyo's 23 central wards is 2045. Thus, Tokyo's population will continue to grow for another 20+ years.

Widespread Depopulation Likely throughout Most of the Country: Estimates of the peak year of population by municipality for each of the 1,884 municipalities available in this projection show that 1,645 (87%) have already reached their peak population in 2020. This means that nearly 90% of cities, counties, towns, and villages across the country have already begun to lose population. Even in the Tokyo metropolitan area, 102 of 202 municipalities, or nearly 50%, and in the Osaka metropolitan area, 121 municipalities, or 85% of 141, are already in a declining population trend. From now until 2035, the population of only 165 municipalities, or 8.8% of the total, will increase. By block, the Tokyo metropolitan area has the largest number of positive growth areas, while more municipalities in the Osaka and Nagoya areas will see their population decline. Most cases of significant population decline, ranging from -15% to -30% or more, are mainly in rural areas. These results further highlight the widening population gap between a limited number of urban areas and rural areas.

Commentary: Looking at these numbers, I am reminded of how Auguste Comte, a 19th century French philosopher, immortalized the phrase "demography is destiny," which has been appearing frequently in the media. It is, therefore, not too surprising to learn that the flow of internal migration seems to be slowing down. As a permanent resident of the Japanese countryside, I only wish that more Japanese people would appreciate the benefits of rural life-especially later in life-to attempt to thwart the overall trend to a certain extent.

I first became aware of the conventional wisdom that leads most Japanese to revere life in Tokyo and often look down on the countryside when I was a foreign exchange student at Tokyo's Waseda University in 1988, where I joined the Shodokai (書道会) or calligraphy club to improve my Japanese. It had many members, and I remember being surprised to learn that every prefecture was represented. Many came from relatively modest backgrounds, and more than a few lived in dormitories near the campus in Tokyo that were subsidized by their home prefectures. While all were proud of their hometowns and encouraged me to visit, they all seemed excited to have finally made it to the big city. A few, like a talented upperclassman artist with whom I became friendly, made a "U-turn" after college to return to his hometown of Arita in Saga to carry on the tradition of his family's pottery business. However, the vast majority stayed in Tokyo after graduation. The magnetic pull of Tokyo, with all its advantages and job opportunities for these talented strivers, was simply too strong for most to even consider returning "home" except for New Year's or the Golden Week holidays in late April / early May.

After college, I was fortunate enough to be awarded a Fulbright Scholarship, which brought me to Kyushu for the first time. One of the requirements of this scholarship was that I had to choose to enroll as a graduate student at a national university other than one in Tokyo, Osaka, or Nagoya. So I was forced to choose a university in the countryside. Since I had never been to Kyushu before, I decided that it would be as good as anywhere. Although I ended up at Kyushu University in Fukuoka, which is a fantastic urban area that certainly does not really qualify as a “rural setting,” it was not too far from the countryside. Little did I know at the time that I would eventually move to Kyushu to live there permanently.

Even before starting Real Gaijin, I wrote several short articles on the subject3. See "Living in Tokyo vs. the Countryside" for more information about the pros and cons of "bright lights, big city" vs. the "slow life" in the "sticks" that suits me just fine. Another, related perspective can be found in "The Growing Problem of Population Concentration in Japan.” For background on the phenomenon of U-turns, J-turns, and I-turns, see "Get Paid by the Japanese Government to Move to the Countryside.”

Finally, for more on my personal journey of relocating from the heart of Tokyo to the radically different environment of rural Kyushu, see "What's It Like to Retire to the Japanese Countryside?”

So, the bottom line is that I am a big proponent of the Japanese countryside. Especially after spending several decades living and working in central Tokyo, at this stage of life (mid-fifties) the Japanese countryside offers a very high quality of life. Don't get me wrong. I appreciate the energy and excitement of Japan's capital. Looking back on the decision to move to the countryside about 5 years ago, I can, though, happily say that it was the right choice. I wish more Japanese people would consider such a move later in life. While everyone is different and it is ultimately a personal choice, living in the countryside has many rewards. Plus, no matter where you go in Japan, you're never more than about 1-1/2 ~ 2 hours away from Tokyo.

What do you think? Are you more of a city person, or is the "slow life" of the country more to your taste? Your answer may change over time, depending on all sorts of factors such as age, job availability, whether you have children to raise, financial means, personal preferences, etc. All answers are completely anonymous, even to the author.

Links to Japanese Sources: https://news.yahoo.co.jp/articles/015d9fba50a7b6a526411e081d220ba1fa6b1b95, https://www.stat.go.jp/data/idou/index.html, https://www.daiwahouse.co.jp/tochikatsu/souken/scolumn/sclm490.html, and 「時論 ~ 市区町村別の将来推計人口から考える」、三井住友信託銀行調査月報、2024年3月号.

#internalmigration #population #migration #populationstatistics #urban #rural #countryside #TokyoMetropolitanArea #東京一極集中 #国内移動 #人口 #転入超過 #転出超過 #首都圏 #地方

Please note that you can subscribe to Real Gaijin for free. If you are so inclined, you can also purchase an annual subscription for a relatively small fee.

However, I understand that even the lowest level of annual subscription allowed by Substack may seem too high for many. If you just want to buy a coffee for Real Gaijin (or maybe a green tea), you can also make a small donation here:

https://buymeacoffee.com/realgaijin

All levels of support - including just liking a particular article and/or leaving a comment - are very welcome. Thanks again for reading.

While Real Gaijin lives in Substack, you can also find Real Gaijin on a few other platforms (listed in alphabetical order).

https://www.instagram.com/real_gaijin_on_substack/

https://www.threads.net/@real_gaijin_on_substack

https://www.tiktok.com/@real.gaijin

https://www.youtube.com/@RealGaijin

https://www.linkedin.com/in/mark-kennedy-5b50b71/

Equivalent to a state or territory

Tokyo's 23 wards that comprise the core section of “Tokyo” were counted as a single city for this analysis.

The online magazine Japan Insider has been "on hiatus" for almost two years now, but who knows, maybe it will be revived sometime in the future. For now, its former self lives on indefinitely on the internet.

Subscribe to Real Gaijin

Unveiling the Real Japan: An American Expat's Inside Look | Hot takes, commentary, and unfiltered insights on life as a foreigner in Japan.

Having lived in big cities for decades, I can understand the attraction, especially for singletons. I can't speak about the Japanese cultural factors; but I think there are two other factors which may reinforce the decline in migration to the cities: firstly, the possibility for those with office jobs to work from home these days. Just avoiding the rush hours trains would make it worthwhile, wouldn't it? The second factor, in my opinion, will be the growing understanding of the harmful effects on health of EMF radiation from wi-fi and cell towers, especially 5G millimeter-waves. I think people will realize that they need to get away from the concentrated and toxic EMF soup in which city-dwellers live. The more rural, the easier.

https://francesleader.substack.com/?sort=search&search=EMF

Good article thanks for sharing. I have heard more about growth & development in Kanagawa recently as well.

But for me specifically I love rural areas far more than city life. Hokkaido, Ibaraki, Chiba, Toyama, Tohoku regions are my favorites.