Discover more from Real Gaijin

Reflections on the Role of "Domestique"

Project Dharma successfully completes more than 1,500 km (900 miles) of cross-country travel on a high-wheel bicycle.

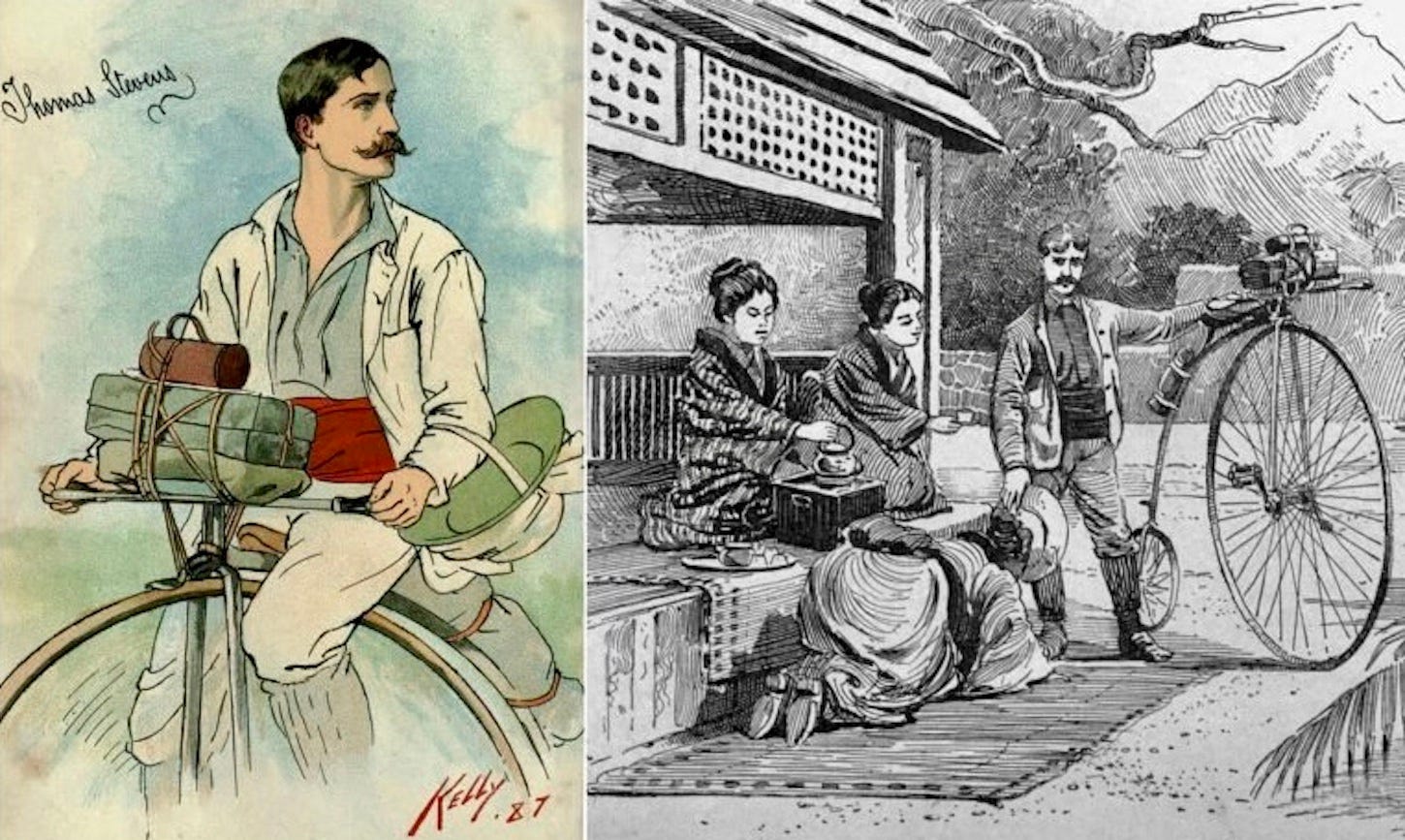

Much like the black-clad stagehand called kuroko (黒衣) plays a supporting role in Kabuki drama by moving scenery and props, facilitating costume changes on stage, and generally helping the main Kabuki actor fulfill their role, I had the privilege of acting as a "domestique" for my old college roommate, Eric Knight '55, as he traveled by high-wheel bicycle1 across western Japan from Nagasaki to Yokohama, retracing the last leg of Thomas Stevens' groundbreaking global bicycle tour in the 1880s. Stevens, the first person to circumnavigate the world by bicycle, set out from his home in San Francisco in 1884 and pedaled east, finally reaching the port of Nagasaki in the fall of 1886. Eric and I set out to recreate the final leg of this epic journey from Nagasaki to Yokohama, and we just completed our trip on October 26, 2023, after 32 days of riding. We called our adventure Project Dharma.

While Project Dharma was not a race, and I am certainly a far cry from an accomplished cyclist playing the role of domestique in the Tour de France, we adopted a broad interpretation of the term to describe my role as the primary support staff for Eric, the lead rider. As the domestique for Project Dharma, my job was essentially to carry supplies and clothing, navigate, and facilitate communication.

Baggage Carrier

Eric and I developed a running joke about how he only had to carry one small pack attached to the "backbone" of his high-wheel bike, while I had to lug two heavy bags piled on top of two overstuffed side panniers. Whenever I mentioned this to interested onlookers, Eric would smile and point to my electric assist battery, which he called a brick.

At first, we struggled to figure out how to tie down all of our gear so that it would not fall off or slide to the side mid-ride. After a week or so on the road, however, we finally got the hang of the optimal method of strapping everything securely to the rear rack with a minimum of bungee cords and laundry line. This was an essential task as we both felt strongly about completing the ride without the use of a support vehicle to carry our gear.

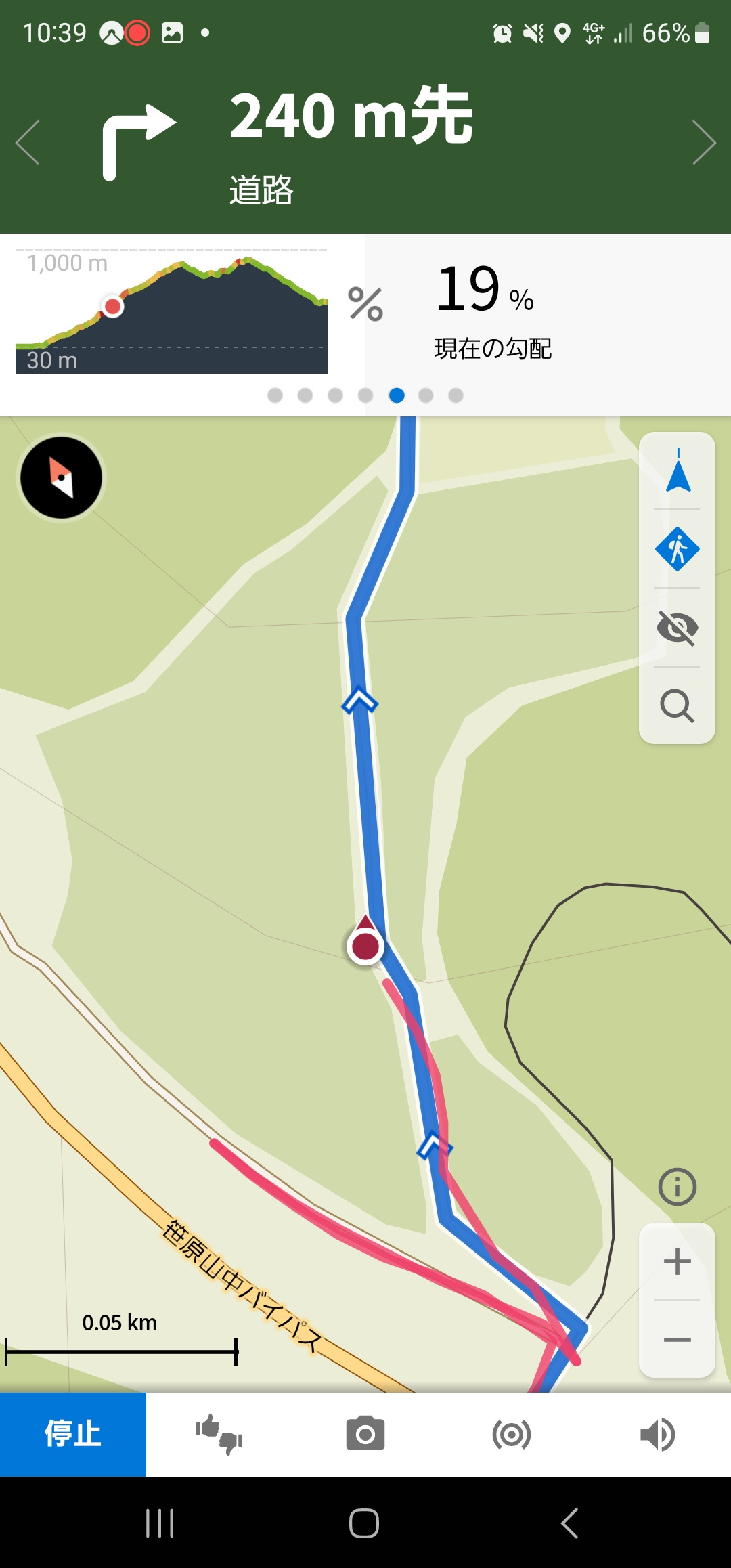

Although Eric and I reduced the amount of luggage to the bare essentials, which required nightly laundry, there is some question as to how much gear Thomas Stevens took with him and how he managed to carry it all. So far, we have not been able to find any information about how he relied on others to help him carry his supplies, except for a single reference to using porters to hoist his bicycle and supplies up the Hakone Mountain Pass from Mishima to Hakone Yumoto, the most challenging part of the entire journey. Although we both had to push our bikes up nearly 1,200 vertical meters that day, with a grade of up to 19% at one point, Eric and I did not rely on porters and made the entire trip under our own power.

Navigation

Given the maze of streets, highways, and back alleys that make up Japan's intricate network of roads--especially in the castle cities, which were designed to be complicated for outsiders--it is now virtually impossible to get around efficiently without some sort of electronic navigation app. That's why Eric and I often wondered how Stevens was able to somehow travel all the way from Nagasaki to Yokohama on his own in the 1880s, in the early days of the Meiji period, just a few years after Japan opened its borders after more than 250 years of being cut off from most of the rest of the world during the Edo period.

While there is evidence that Stevens relied on an early edition of a guidebook called Murray's Hand-Book Japan, which included detailed maps, some Japanese historians we consulted along the way offered a relatively simple explanation. At the time of Stevens' visit, there was essentially only one main road. (Actually, there were three major "highways" between Nagasaki and Yokohama, including the Nagasaki Kaido or "Sugar Road" in Kyushu from Nagasaki to Moji, the Sanyodo between Shimonseki and Kyoto, and the famous Tokaido that connected Kyoto to Edo (now Tokyo). So it was probably much easier for Stevens to navigate his way around Japan than it was for the two of us!

We relied on the German app Komoot, which is optimized for cyclists. This app is especially useful for planning rides, as it measures distance and graphically displays vertical elevation. Waypoints can be added to modify detailed routes and avoid particularly challenging terrain.

Overall, Komoot did an admirable job of keeping us on track while steering us away from roads with heavy truck traffic. However, we found that Komoot was not perfect. On more than a few occasions, it led us down dead ends, to stone steps where the on-screen directions said there should be a road, and to paths through an overgrown forest. Compared to Google Maps, which is optimized for cars and pedestrian traffic, Komoot also seems to be lacking in terms of navigating to specific addresses in Japanese. We often had to resort to Google Maps for the "last mile" and/or guess an approximate location using Komoot's graphical map interface.

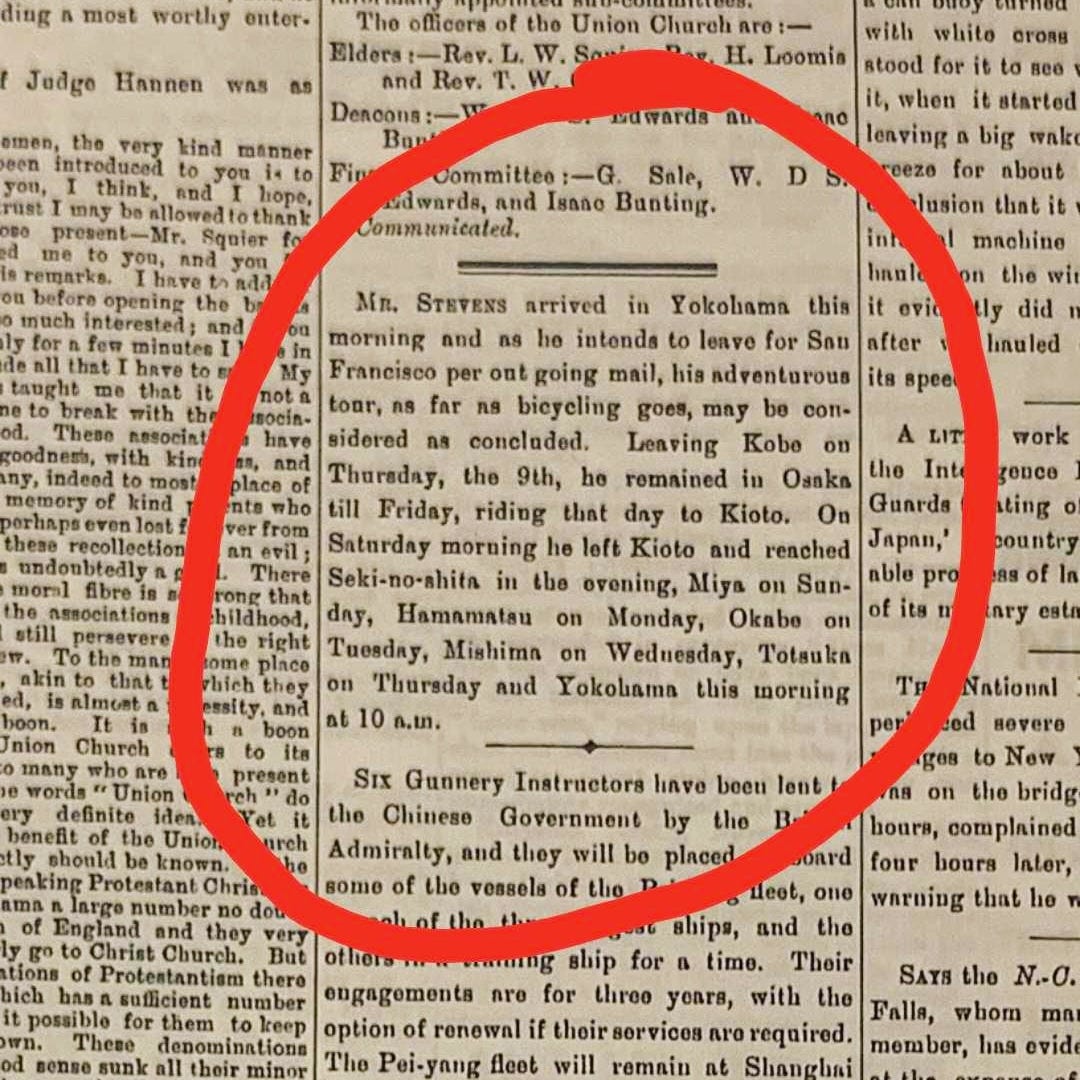

Even assuming that Stevens did not have to worry about straying from the main road, there is still the question of his reported speed. According to a record of his route from Kansai to Yokohama published in a contemporary account of the journey in an English-language newspaper, Stevens is said to have traveled from Kobe to Yokohama at an almost superhuman pace. Even the most accomplished modern cyclists, unencumbered by heavy equipment, would be hard-pressed to travel that fast. It is true, however, that Stevens had about 20 years on us, was probably in optimal physical condition, having been on the road for more than 2-1/2 years before reaching Japan, and was probably riding up to 12 hours a day (compared to our pace of only about 6 ~ 8 hours a day). So, maybe we were just slow. However, Stevens would have encountered cobblestones and other sub-optimal road conditions.

Stevens must also have been slowed down by curious onlookers. No matter where Eric rode, we were soon approached by curious bystanders, most of whom had never seen a high-wheel bicycle before. In Stevens' day, almost no Japanese had ever seen a bicycle of any kind, let alone a Western foreigner. So, he must have attracted even more attention than Eric.

Here is an example of an impromptu demonstration in a convenience store parking lot:

Perhaps the reported speed of Stevens' trip will forever remain a mystery, but Eric and I can honestly attest that we rode the entire way (except for a ferry from Moji to Shimonoseki; Stevens also took a boat across the Kamon Kaikyo Straits that separate the main islands of Kyushu and Honshu). We averaged about 50 to 70 km (31 to 44 miles) per day, which may not sound like much. Considering the elevation changes throughout the mountainous country and the traffic in the big cities, such a pace was actually not bad.

Related to navigation, one question we often got was how to determine where to stay each night. While we did make reservations ahead of busy weekends and holidays, we often took a break in the middle of the day and ran various scenarios with Komoot to determine how long we could ride before sunset, which ended up being around 5:15 p.m. toward the end of our trip, and then searched online for suitable accommodations. While we were particularly fortunate to stay with a personal friend for one night in Kyoto, which turned out to be one of the highlights of the entire trip, most nights we stayed in inexpensive minshuku (motel-level inns) or Japanese-style "business hotels," some of which crammed two twin beds into a 13-square-meter (140-square-foot) room!

Oddly enough, we only stayed in the same hotel chain more than a few times over the course of 32 nights. Over time, Eric and I came to prefer hotels with tatami mats, where there was plenty of room for both our gear and a couple of futons. While the cost of such accommodations varied, at the low end we paid as little as 2,500 yen (US $17) per night per person—including breakfast—for a comfortable room. On average, it was not difficult to keep the budget well under $100 per day per person, including all meals. Especially with the recent devaluation of the Japanese yen against the USD, Japan is now a bargain—especially for hotels and meals. The cost of gas and transportation in general is still high in Japan, but Eric and I simply used our own pedal power to get from point A to point B for free!

Communications

Another facet of Stevens' journey that is open to question is how he managed to communicate along the way. At the time of his adventure, Japan had only been opened to the West for less than twenty years, and it is doubtful that many people would have been able to communicate in English2. Stevens may have relied on some rudimentary dictionaries, but it is doubtful that he was able to learn much Japanese. However, this may be the key to understanding how he was able to communicate.

Stevens probably learned at least a few words of Japanese to communicate his most basic needs of shelter for the night, food, and an occasional bath, which were probably more readily available in Japan than in any other place during Stevens' 2-1/2 year journey around the world.

However, it is unclear how Stevens would have received roadside assistance if he had needed help with the bike. Eric and I needed help fixing technical problems a few times during our trip, and we were lucky enough to get help from bicycle mechanics such as Toma-san (ジテンシャドコロポタリングゥ・自転車処 ぽたりんぐぅ) at Potteringood's Bicycle Station in Sakai, Osaka.

According to his own diary, Stevens usually stayed at a small roadside inn called a yadoya (宿屋). It would have been the modern equivalent of a restaurant with a few rooms upstairs. Eric and I had the pleasure of staying at such an inn in Ako Onsen called Hatsune, which is essentially a biker bar with a few rooms. Although there is an old motorcycle from the U.S. prominently displayed in the downstairs bar/restaurant where a band would play, there were no Hell's Angels during our visit. With rain forecast for the day after we checked in, we decided to stay there two nights in a row to give Eric time to recover from some leg pain and to avoid having to ride in the rain. It turned out to be one of the highlights of the trip, as the innkeepers were extremely nice, lent us their car for the day, and are excellent cooks.

One of my jobs was to find such local accommodations, often not listed on the major travel sites, and then facilitate routine communication in Japanese. Having spent more than a quarter of a century living and working in Japan, I have a business-level fluency in Japanese. (However, there will always be room to improve my level of proficiency.) As a result, Eric was able to relax a bit when it came to communicating his needs (e.g., one night when he needed to purchase medical supplies to treat pain in his Achilles tendon, etc.).

While we met a few people along the way who were able to communicate effectively in English, most were more comfortable speaking in Japanese and allowing me to interpret for Eric. This made it possible to have all sorts of impromptu conversations with a wide variety of people who were interested in Eric's high-wheel bicycle. We routinely drew crowds in the parking lots of convenience stores, supermarkets, and bike stores, and other shops. Almost invariably, innkeepers would take an interest in the bike and ask for a quick demonstration before we left in the morning.

Eric and I quickly developed a routine for answering the most common questions, such as "How do you get on the bike?", "How do you get off the bike?", "How fast can you go?", "How old is the bike?", "For how long (hours) do you ride a day? "How far do you ride each day?" etc. Being able to have a real back and forth discussion like that certainly made it more fun for the bystanders and for us. Stevens must have struggled to communicate, unless he had the help of some unknown bilingual assistant whose name has been lost to history.

While the two of us collaborated on a short write-up of our daily activities each night, I was also responsible for tracking our progress and adding photos to the app Relive and updating our official social media channels via Instagram, Facebook, and the website for CountryRoadsJapan.com. On particularly long rides it was difficult to find enough time to get cleaned up, eat dinner, do laundry, and then post content, but we decided early on to maintain this disciplined routine.

The spontaneous feedback was overwhelmingly positive, which encouraged us along the way. One of our video clips, taken on the ferry from Miyajima back to the mainland near Hiroshima, somehow generated more than 100,000 views. We would like to know why this particular clip went viral, but we were happy that it did!

Support

So while it may have been a stretch to apply the cycling term domestique to my role in Project Dharma, Eric and I adopted a loose interpretation of the term to include the tasks of carrying luggage, providing navigation, and facilitating communication.

With the help of a random truck driver who gave us some drinks at a 7-11 parking lot outside Kurashiki in rural Okayama Prefecture during one of our breaks, we even made a couple of short videos for Instagram to explain my role. Please check them out:

English Version:

Japanese Version:

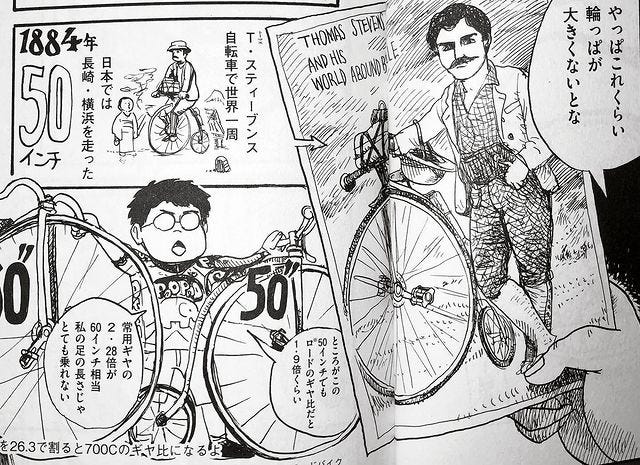

The observer who helped us film these two clips was a good example of the variety of interested people we met across the country. A few days before the end of the ride, Eric and I were honored to receive an outstanding pen and ink drawing from professional manga artist Kurodaiou (https://www.instagram.com/kurodaiou/), who uploaded the following image on Instagram:

This drawing of the two of us perfectly captures how Eric and I traveled through Japan as a team. Just a few days into the trip, we became aware of this artist and their previous work, which predates Project Dharma and depicts Stevens' historic journey in Japan.

While Project Dharma provided more than enough adventure on its own, the opportunity to meet such a diverse group of people in the western half of Japan proved to be the ultimate reward for acting as a domestique every day for an entire month. We wonder if Stevens benefited from someone, or more than one person, acting in this capacity whose identity has been lost to history. We may never know for sure, but it is fun to think about.

To learn more about Project Dharma, please refer to the following links:

CountryRoadsJapan Website: https://countryroadsjapan.com/home

CountryRoadsJapan Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/countryroadsjapan/?hl=ja

CountryRoadsJapan Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CountryRoadsJapan

There are many terms for this type of bicycle, which is characterized by a large front wheel and a small rear wheel. In the U.S., such bicycles, which were popular in the 1870s and 1880s, are known as "high-wheel bicycles," while in the U.K. and current and former Commonwealth countries they are called "penny farthings.” In Japan, these bicycles were sometimes called "ordinary" (オーディナリー), but the most common term was daruma jitensha (ダルマ自転車). The choice of the Japanese spelling of the word dharma or daruma (ダルマ) to describe this type of bicycle with its oversized front wheel must have been related to its connotation with the dharma wheel, a common symbol in Buddhism. The word jitensha (自転車) means bicycle in Japanese.

It is unclear whether Stevens was fluent in languages other than English. He was born in England and emigrated to the U.S. at an early age.

Subscribe to Real Gaijin

Unveiling the Real Japan: An American Expat's Inside Look | Hot takes, commentary, and unfiltered insights on life as a foreigner in Japan.

This adventure is an amazing accomplishment about bringing history to life!

What a splendid article, Mark! You are a great writer, and the adventure was one in a million to have and to read about! Just wonderful!